In addition to being the cause of a number of diseases, the Epstein-Barr virus is also responsible for certain forms of cancer. Researchers from the University of Basel and the University Hospital Basel have published a study in the journal Science, presenting new evidence that indicates inhibiting a particular metabolic pathway in infected cells can reduce the probability of latent infection and, consequently, the risk of developing a disease in the future.

Pathologists Anthony Epstein and Yvonne Barr reported their finding of a virus exactly 60 years ago, and it has held their names ever since. Being the first virus to be shown to cause cancer in people, the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) made scientific history. This member of the herpesvirus family was identified by Epstein and Barr from tumor tissue, and they went on to show in other tests that it could cause cancer.

An estimated 90% of adults are infected with EBV, which usually causes no symptoms or sickness in them. The majority of individuals are carriers of this virus. Although many people don’t get it until puberty, about 50% have it before the age of five. Acute viral infection can result in glandular fever, popularly referred to as “kissing illness,” which renders affected people immobile for several months. Apart from its carcinogenic characteristics, the pathogen may also have a role in the onset of autoimmune disorders like multiple sclerosis.

Neither a medication nor a licensed vaccine can presently effectively block EBV from entering the body. Recently, a study team from the University Hospital Basel and the University of Basel has announced a promising first step in stopping EBV. The journal Science has published their findings.

EBV takes control of infected cells’ metabolism.

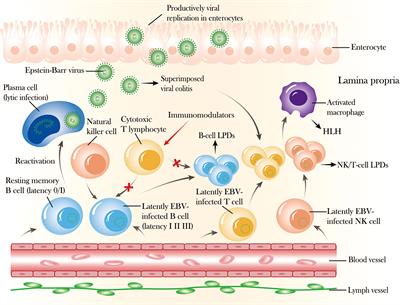

Under the direction of Professor Christoph Hess, a team of Department of Biomedicine researchers has found the process by which immune cells infected with EBV—also known as “B cells”—undergo transformation. The infection must go through a process known as “transformation” if it is to last and finally result in disorders like cancer. More specifically, the scientists discovered that the virus raised the enzyme IDO1 synthesis in the infected cell. As a result, compared to their normal levels, the mitochondria—the energy-generating centers of infected cells—see an increase in energy output. The quick metabolism and fast multiplication of the altered B cells generated by EBV call for the use of these extra energy sources.

From a clinical perspective, the researchers concentrated on a subset of patients who had received organ transplants and afterwards had blood malignancy caused by EBV. To prevent organ rejection following transplantation and weaken anti-tumor immunity, medication must be administered. Consequently, this facilitates EBV’s ability to take control and develop post-transplant lymphoma, a type of blood cancer.

In their recently published work, the researchers demonstrated that EBV upregulates the enzyme IDO1 months before post-transplant lymphoma is identified. This discovery could aid in the creation of disease biomarkers.

A second opportunity at a drug failure

Previously, researchers created IDO1 inhibitors with the intention of treating existing cancer. However, sadly, this has not proved effective. To put it another way, inhibitors against this enzyme have previously undergone clinical testing,” says Christoph Hess. As a result, this class of medications may now be given another chance in applications meant to lessen EBV infection and hence treat disorders linked to EBV. In fact, IDO1 inhibition with these medications decreased B cell transformation and, consequently, the viral load and lymphoma growth in mouse tests.

Transplant recipients routinely receive medications against several viruses. Hess claims that as of right now, there is no particular treatment or prevention for Epstein-Barr virus-associated illness.

Research Source

University of Basel

Research Resource Article

New approach to Epstein-Barr virus and resulting diseases

What a horrible two years it’s been! 😫

It took some time to diagnose the problem, but I have chronic Epstein-Barr virus, or at least EBV that flares up periodically. When I was 19, I had my first mono. After 16 years, in December 2020, I tested positive for an active infection (thanks to my doctor for checking it out). It was believed to go away in a few months, but I was still quite weary all the time. After six to eight months, there was another positive test, and a few days ago, there was yet another, this time for an active infection, with much higher numbers.

I have no idea what to do. Does anyone else have to deal with this here?

The only information I could find on Google stated that patients with persistent EBV receive “hematopoietic stem-cell transplants.” Although I’ve never taken an antiviral, I am aware that they can have unpleasant side effects and take a while to start working (if at all).

Naturally, I’ll get to follow up with my doctor about this at some point, and I’m eager to hear what his course of action is. Perhaps need to consult a professional in infectious diseases? I’m not sure.